NORTH AFRICA, MIDDLE EAST AND CENTRAL ASIA

Translated from the French by Mattias Ripa (Satrapi’s real life husband) and Anjali Singh

Marjane Satrapi’s memoir Persepolis broke new ground, by exploring her experiences during and after the Iranian Islamic Revolution and the Iran-Iraq war of the late 1970s and 1980s, in the form of a graphic novel. Published in the early 2000s, by 2018 it had sold more than 2 million copies.

As Satrapi writes in an Introduction to the book: “Since [the Islamic Revolution] this old and great civilization has been discussed mostly in connection with fundamentalism, fanaticism, and terrorism. As an Iranian who has lived more than half of my life in Iran, I know that this image is far from the truth.”

I ordered my copy from my local Southwark library. Really, it is two books, or even four books, as it includes what was originally published in France as Persepolis I and II (The Story of a Childhood) and Persepolis III and IV (The Story of a Return). I’d taken it out of the library before, but hadn’t got round to reading it, assuming, I guess, that because of its themes it would be heavy-going and hard work. However, once I’d decided I was going to embark on my global cultural tour, I grabbed a copy for the second time – and actually read it. Within just a few pages I was gripped….

….Although my only gripe was that the text is teeny tiny, even with my old-person reading glasses on.

The book is aimed squarely at a Western audience, and is designed to break down stereotypes and challenge misinformation, as well as entertain. Unsurprisingly, the book was banned in Iran. Satrapi herself settled in France in her 20s, although her enduring love for her native country shines out clearly from her writing.

Although I’m not usually a fan of the comic strip format, the device makes the sometimes challenging themes of Satrapi’s story hugely accessible. Satrapi is feisty and funny, describing her experiences of growing up, which veer between the universal and the specific.

Satrapi describes how as a small child her ambition in life was to become a prophet. She believed that she was visited by God, although his pronouncements could be prosaic: “Tomorrow the weather is going to be nice. It will be 75 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade.”

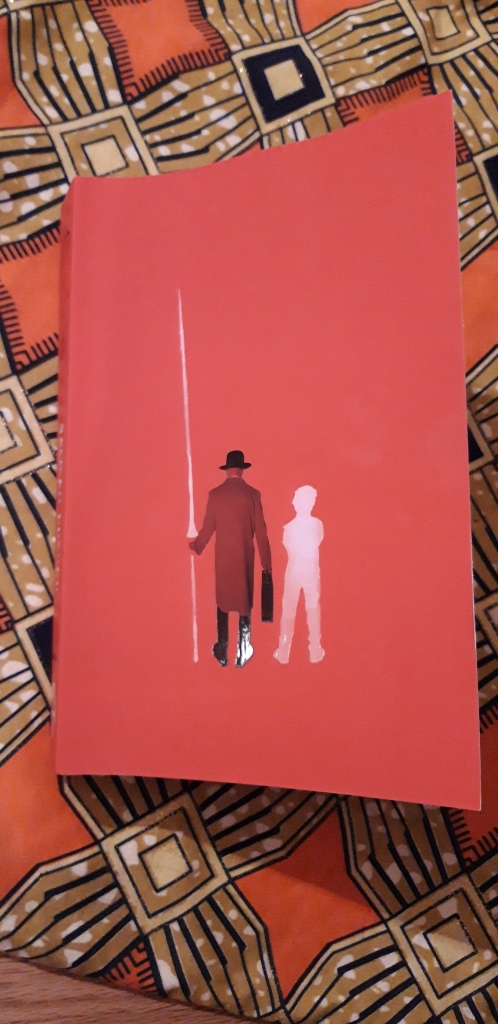

The illustrations, an integral component of the book, are great: evocative and, again, often disarmingly funny. Satrapi is brilliant on facial expressions. Black and white, stark and combining elements of both her Iranian and her adopted cultures, they effectively illuminate Satrapi’s experiences.

Satrapi’s experience in Iran, of course, was in many ways atypical. Her family were part of an educated elite, and had the money to send her to Europe for several years in her teens, to take trips to Europe and Canada themselves, and to pay for Satrapi to move to France to study in her twenties.

So she had a comparatively privileged lifestyle, but that is not to undermine or understate the difficulties Satrapi faced growing up during a time of repression and devastating conflict. And she effectively conveys the horrific toll it took on the people of Iran as a whole. This includes the sudden proliferation of nuptial chambers (as Satrapi explains, when an unmarried shi’ite man dies, a nuptial chamber is built for him so the dead man can, symbolically at least, gain carnal knowledge) and the huge number of streets renamed in honour of fallen ‘martyrs’.

In addition to being a coming of age story and a political memoir, the book is also a tale of familial love. Satrapi’s warm, loving, secular parents were endlessly supportive and caring, and her filthy-mouthed granny is an appealing character (who, incidentally, attributed the pertness of her elderly breasts to a daily 10-minute dip in ice water). Illuminating and entertaining, and a quick read, I wholly recommend this illuminating book.