DENMARK, EUROPE

Translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken

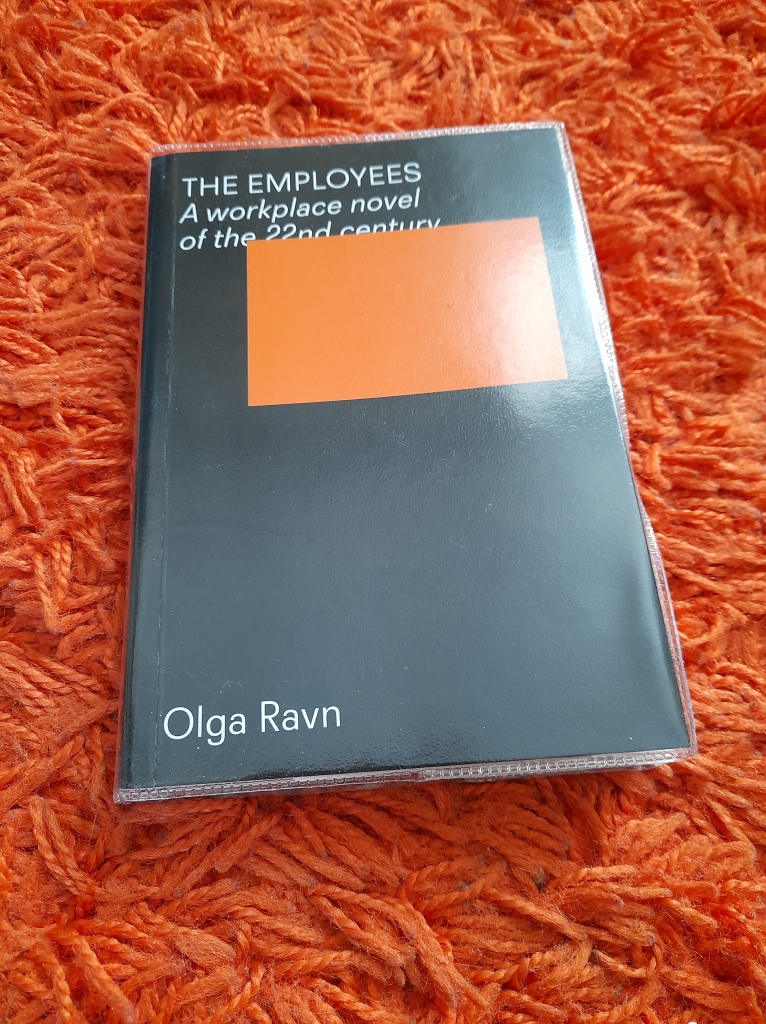

(book 1 of my #20booksofsummer21)

I just finished the first of my 20 books of summer (hosted annually by Cathy at 746 books). The Employees is a very short novel (135 pages in the English translation) by Olga Ravn, who is best known in her native Denmark for her poetry. Ravn’s oblique novel (published by Lolli Editions) has been shortlisted for the Booker International Prize (with the winner to be announced on 2 June). The book has been expertly translated by Martin Aitken, who also translates from Norwegian, notably having translated Hanne Ørstavik’s Love, which I reviewed in 2019.

The Employees is set aboard a space vessel (the Six-Thousand Ship) in the not-too-distant future, at some point during the 22nd century. In an experimental take on epistolary fiction, the book comprises a series of employee statements, which vary in length from a single line (“Statement 021: I know you say I’m not a prisoner here, but the objects have told me otherwise”) to a couple of pages.

We are initially thrown in media res, trying to piece together meaning from this jumbled bundle of bureaucratic documents, which appear out of sequence: the book opens with statement 004, which is followed by statement 012, and so on, initially giving the novel a jigsaw-like aspect. And that is before we even begin to consider the content of the statements, which feels equally confounding, as we attempt to shape the information that is being drip-fed to us into some kind of coherence.

A narrative does begin to emerge, however. The aim of the written statements, as laid out in an opening page replete with futuristic corporate jargon, is to evaluate the way employees relate to certain objects, and the rooms in which they are placed, “to gain knowledge of local workflows and to investigate possible impacts of the objects … illuminating their specific consequences for production.” Anyone who has worked for a big corporation will be aware of the semantic nihilism and euphemistic double-think of business-speak, which is particularly rampant during those ubiquitous annual appraisal and objective-setting exercises, or during periods of “change management”. Ravn identifies the particular form of existential horror thrown up by such workplace conventions.

From the start we know that the ship contains mysterious objects (“It’s not hard to clean them. The big one I think, sends out a kind of a hum”), and that some of the employees are more human than others (“He said ‘You’ve a lot to learn my boy’. An odd thing to say, seeing as how I was made a man from the start.”) The objects seem to be contained in just two rooms, and to to be alive, or at least faintly sentient. Meanwhile, some of the employees have been ‘modified’ in some way: as Statement 015 informs us, “I’m very happy with my add-on … I’ve had to change completely to assimilate this new part that you say is also me. Which is flesh and yet not flesh. When I woke up after the operation I felt scared, but that soon wore off”.

The book initially works as a statement about the automation of working practices, and the dehumanisation inherent to a long-hours culture and a focus on productivity over all else. “Statement 044: The first smell that disappeared was the smell of outside, of the weather, you could say. Of fresh air. … The last smell that disappeared was the smell of vanilla. That, and the fragrance of my child when I would bend over the pram to pick him up”.

The statements gradually and unevenly progress chronologically, over an 18-month period during which the testimony has been taken. There is a reference to the room with the objects as a “recreation room”, references to new dreams proliferate, along with smells, music, light, recovered memories of earth and unexpected emotions: “You tell me: This is not a human, but a co-worker. When I began to cry you said: You can’t cry, you’re not programmed to cry, it must be an error in the update.“

As time goes on, signs of conflict between employees begin to emerge, and the novel becomes a meditation on what it means to be human, and what it takes for a life to have meaning. Ravn combines genre tropes and a deft knowledge of corporate cliché to concoct a new take on sci-fi, which combines the uncanny with a sometimes touching study of burgeoning humanity.

Interestingly, the book opens with a dedication to artist Lea Guldditte Hestelund “for her installations and sculptures, without which this book would not exist”. It is written, then, in response to this recently exhibited work, which has the “character of a physical science fiction story”.