AFRICA

As I’m trying to work my way through books, film and art from across the world, it makes sense to ensure that I’m not spending too much time in one region. I need an even spread of countries from all five of the regions that I’ve divided the world -roughly evenly – into.

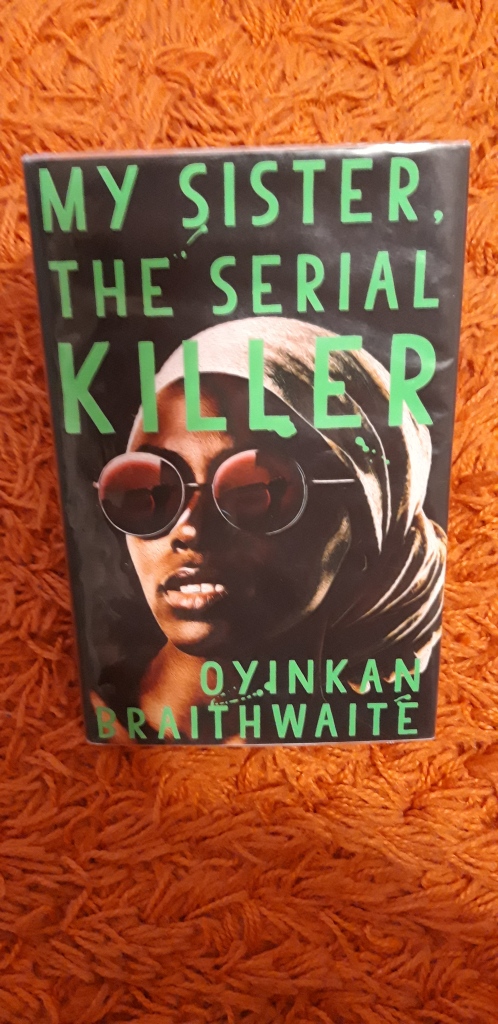

So I’m back in Africa, and as far away from the tone of my last book from the continent as you get. Oyinkan Braithwaite’s My Sister, the Serial Killer is a quick, fun read, and a book that was long-listed for the Booker Prize 2019.

Oyinkan Braithwaite is a Nigerian writer. I recently read a quote from Elleke Boehmer, Professor of World Literature in English at Oxford University, describing the “Chimamanda glamour effect”. It may be that the huge success of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who won the Orange Prize in the UK in 2007 for Half of the Yellow Sun, has led to a surge of interest in Nigerian female writers.

My Sister, the Serial Killer opens with Korede, a nurse, helping to cover up a murder. Korede’s glamorous, social media-obsessed, fashion-designer sister Ayoola has killed her latest boyfriend (he is not the first), and older sister Korede feels compelled to protect her. The young women come from a wealthy background that from the outside looks privileged, but there are dark family secrets lurking beneath the surface. Meanwhile, Korede has a massive crush on her hospital colleague Dr Tade, and when Ayoola notices him, Korede starts to fear for his safety.

Beautiful and beautifully dressed, with a sadistic enjoyment of death and a potentially incriminating love of Snapchat and Insta, Ayoola is a great character. She reminded me of Villanelle in recent TV series Killing Eve. ‘”We were in the room together and he suddenly starts to sweat and hold his throat. Then he starts to froth at the mouth. It was so scary.” But her eyes are on fire, she is telling me a tale she thinks is fascinating. I don’t want to talk to her but she seems determined to share the details.’

I also enjoyed the little insights into Nigerian culture that the reader is given, which include widespread official corruption, and discovered a new drink that I’d like to try, the chapman.

The plot moves along very quickly, with short punchy chapters, sometimes barely two sentences long, and never longer than a handful of pages. If I had to criticise, I’d have to admit to finding the ending a little flat, but overall this was a really enjoyable read.

Other female writers from Nigeria worth checking out include Ayobami Adebayo, whose novel Stay With Me was recommended to me by my friend Emily, and which we read as part of our long-running book club. I’ve also heard praise for Nnedi Okorafor’s sci-fi novella Binti.